Beyond the immediate economic and social crises that dominate the ever shortening attention span of today’s news media, climate change remains an ongoing issue that continues to fester away in the background. Once relegated to the margins, climate change has most assuredly made it into the mainstream. To put it simply, debate around climate change essentially revolves around a dispute amongst various vested interest groups who are all pushing their own particular agenda and seeking to maximise their position. It can be seen as a contest between environmental degradation and humanitarian disaster versus economic interests, political power and profits. This debate is also shaped by the fact that no immediately dramatic events have been conclusively linked to climate change, which creates the space for doubt in the public mind. And doubt is always open to exploitation. The immediacy of danger also informs how we respond – we all know that certain things are probably bad for us or may be potentially dangerous but if the effects take decades to harm us then the human mind seems quite willing to ignore it; say, instead of giving you cancer in 30 years time, smoking a cigarette killed you tomorrow then our response to the matter is very different.

Obviously the big polluters (countries and corporations) have a large incentive to downplay or dismiss the issues surrounding climate change and pollution but thanks to their rather murky track-record in responding to environmental problems in the past their credibility on this issue is very low. A classic tactic such large and well funded corporate interests tend to deploy is to undermine the validity of the arguments presented by the opposite side through the use of scientific studies that appear to refute claims or otherwise cast doubt upon them. Although science is presented in the popular imagination as a purely objective process it can be filtered through an ideological prism when circumstances demand. If an energy company is funding researchers (or universities) examining, for example, the effects of pollution on marine life then there will be a great deal of unspoken pressure to ensure that the results do not embarass the company funding your work. To do so would almost certainly affect future contributions from industry towards both you and your university, not to mention the potential damage to your career prospects. Unspoken bias creeps in. The report conclusions can be skewed in a certain direction. And the usual way to ensure that your research doesn’t come back to haunt you later on is to include a section stating that these findings are based upon available data but that more analysis needs to be done over a much longer timeframe which may alter the conclusions. (For more see this article by Professor Brian Martin.) Big business, money and science make for uneasy partnerships.

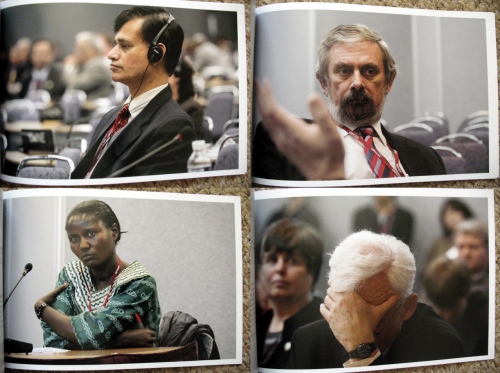

The images that comprise this book were made during the 11th United Nations Conference on Climate Change, held in Montreal during 2005 by Joel Sternfeld, the seminal photographer whose legacy in terms of the photographic visualisation of the American landscape is writ large. But information about the purpose of the conference itself is lacking in the book. The UN stated that they regarded this conference as particularly important because it saw the coming into force of the Kyoto Protocol. (Information about the conference can be found on the UN website.) Yet even a cursory glance at the agenda for the conference will reveal that a good deal of the schedule was taken up with proceedural matters, bureaucratic niceties, acknowledgements of contributions made by member states and rather uninspiring, dry legalese about the implementation of various sub-sections of the Kyoto Protocol. Lets be honest here; the bulk of the conference itself sounds quite dull and boring. For a topic of such apparent global importance it is surprising that there appears to be no real urgency about finding a lasting solution. Public pressure expects that policy makers will combat climate change as well as preserve living standards (in developed countries). So what’s with all the foot dragging?

A useful way of understanding this is to have an awareness of how bureaucracies and politics operate in the context of such issues of widespread public concern. Once an issue becomes mainstream, pressure groups tend to be sucked into various bureaucratic systems where the promise of real power and influence to achieve their goals is too tantalising to resist. Its a classic trap. If environmental groups reject calls to work with government/bureaucracies to assist in changing the system they risk the losing public support they have built up over the years. Compromises are made. The earlier radicalism and public mobilisation outsider groups and organisations once possessed are now controlled and negated by the bureaucratic structures they are now working with. Politics works in a similar vein; once public opinion shifts towards an acceptance of something that was previously dismissed as crazy, the language and policies of politics moves to appropriate these issues in order to woo potential voters and support. Simply put; the rules of the game are set by the existing power structures (bureaucracies/politicians) and these systems operate to hollow out and negate the threat to them by incorporating and controlling calls for change that pose a challenge to the status quo. This results in a situation where the language of change becomes bereft of meaning and is reduced to political sound-bites and the commissioning of inaccessible phone-book sized studies and reports stuffed with jargon that makes it difficult for the public to follow. (This is not meant as a criticism of any particular NGO or environmental group – this is just how bureaucracies and politicians operate on a vast range of issues in order to maintain their power and position.)

Once an issue such as climate change becomes mainstream a whole new structure of environmental-bureaucracy is created whose sole purpose is paper shuffling, attending conferences, passing resolutions, creating international legal frameworks, drafting press-releases and ensuring that national governments are seen as global team players. A perception is created within the wider public that something is being done at an official level so therefore there is no need for them to care about this issue anymore. Similarly through incorporating vague policies and talking the talk about environmental issues (which are usually ignored by those in power in the pursuit of short-term electoral gain and popularity) politicians ensure that the issue is managed within the structure of the existing political system and does not become a threat to the way they do business. Lip service is paid to environmental issues in press statements and political sound bites but substantive and lasting change can often be more difficult to find.

Turning to the book, Sternfeld combines portrait images of conference delegates with a series of brief news reports dealing with climate change events, beginning in 1957 with the first indications that the oceans might not be able to deal with increased CO2 emissions. The images are all close-up, head and shoulders portraits of conference delegates that appear to have been made during the proceedings. All of the individuals depicted (with the exception of a solitary Asian man who is fast asleep) exhibit the signifiers of gravitas and pensive concentration. None of them appear to acknowledge the camera; to do so would show that they were not paying sufficient attention to the important proceedings taking place. Public perception would lead us to believe that such conferences are full of committed and concerned advocates (and there are undoubtedly some present) but most of the participants represent various national, bureaucratic, environmental and corporate interest groups who are all there to ensure that they maximise the benefits to their own organisations.

Accompanying these images, the brief news reports serve as a catalogue of scientific predictions, unpredictable weather incidents, melting ice caps, ozone layer depletion, droughts and potential epidemics to come all related to Global Warming and climate change. Sternfeld creates a narrative in which the reader-viewer directly links the faces of the conference participants to the accompanying text. Yet, Sternfeld’s images do not show individuals responding to such events. (Of course, it should be recognised that some of the media accounts selected by Sternfeld tend to be overly sensationalist in nature which heightens the contrast.) Instead, what we see are images of participants in a Montreal conference room distanced from the immediate effects of catastrophe in the middle of a negotiation process. Even the gestures within the portraits seem to convey a sense of concern, and even horror, to the viewer at what they are hearing and seeing at the conference. But in reality we don’t know in what context these gestures were made; boredom, annoyance and tiredness are all equally valid readings. Ambiguity pervades this work which creates more and more questions about what I am seeing here.

Even the title, When It Changed, raises a further questions. What exactly is the It he refers to? A global response? The actions of business? Public attitudes? And how has it changed – for the better or the worse? None of these questions are answered by Sternfeld within the book. This ambiguity is further enhanced by Sternfeld’s own words on this work which is presented on the Steidl website as a visual legacy for future generations about current decision making processes. A more telling indication can perhaps be found in this article by the New Yorker about his later work iDubai, which states that Sternfeld began to believe that “even if we could solve climate change, it would simply allow us to consume the world and the world’s resources in some other way”.