By the mid-1990s, North Korea was in deep trouble. It looked as if the isolated communist bastion was on the verge of collapse. A number of crises all happened in quick succession that each threatened to cause the regime to fall apart. Firstly, you had the fall of the USSR and the rest of the communist bloc, who North Korea had depended upon. Food and fuel provided by the friendly communist world, at bargain-basement prices, had been key to the regime’s survival. Once that dried up, North Korea was screwed.

The economy fell apart and complete social collapse was on the cards. It didn’t produce enough food to feed its people (only 20% of its land is suitable for agriculture) and now it couldn’t pay for imports. Added to this, 1995 and 1996 saw a series of floods which destroyed both crops in the fields and centralised grain stores. 1997 brought a drought. The result was famine. The exact numbers of deaths is unknown, but estimates range from 900,000 to 3 million people died. Whatever the precise number is, it is safe to say that vast numbers of people died.

The economy fell apart and complete social collapse was on the cards. It didn’t produce enough food to feed its people (only 20% of its land is suitable for agriculture) and now it couldn’t pay for imports. Added to this, 1995 and 1996 saw a series of floods which destroyed both crops in the fields and centralised grain stores. 1997 brought a drought. The result was famine. The exact numbers of deaths is unknown, but estimates range from 900,000 to 3 million people died. Whatever the precise number is, it is safe to say that vast numbers of people died.

Then 1994 saw the arrival of another existential crisis for North Korea; the death of the founding father, Kim Il Sung. A charismatic dictator, he had established an all-pervasive personality cult that demanded complete worship of the self-styled Great Leader by the entire population. His death saw the rise of his untried and untested son, Kim Jong Il (known as the Dear Leader) to take his place. Leadership transitions in dictatorships are always fraught with danger as all political legitimacy in such states is tied to the person of the leader. Therefore loyalty to the Dear Leader could not be assured, particularly when millions were starving.

Then 1994 saw the arrival of another existential crisis for North Korea; the death of the founding father, Kim Il Sung. A charismatic dictator, he had established an all-pervasive personality cult that demanded complete worship of the self-styled Great Leader by the entire population. His death saw the rise of his untried and untested son, Kim Jong Il (known as the Dear Leader) to take his place. Leadership transitions in dictatorships are always fraught with danger as all political legitimacy in such states is tied to the person of the leader. Therefore loyalty to the Dear Leader could not be assured, particularly when millions were starving.

In response, Kim Jong Il intensified the songun policy. Basically the military first songun involved channelling all resources into the armed forces at the expense of everything else. This strategy was tantamount to applying the simple guns versus butter macroeconomic economic model to a closed economy. The stark choice the regime faced was to either feed the people or concentrate everything on maintaining a strong military. Resources were limited. They chose the military option. Widespread suffering, starvation and death was the result.

Everything had to be sacrificed in order to keep a strong army. Thing else mattered. There was a terrible and ruthless logic to this approach for the regime. The army was needed to prevent both internal and external threats from causing the regime to fall apart. Firstly, by making sure that the armed forces were well fed and insulated from the collapse it meant their loyalty could be counted upon.

Everything had to be sacrificed in order to keep a strong army. Thing else mattered. There was a terrible and ruthless logic to this approach for the regime. The army was needed to prevent both internal and external threats from causing the regime to fall apart. Firstly, by making sure that the armed forces were well fed and insulated from the collapse it meant their loyalty could be counted upon.

When things start to go wrong in a dictatorship, there is always the possibility that angry, disgruntled and poorly fed soldiers might stage a coup and pull everything down. By letting the military know that their best interests were served by remaining loyal to the Kim dynasty, that possibility was diminished. The interests of the military and the new leader were now one and the same. This also meant that they could be relied upon to crush any protest or dissent amongst an increasingly desperate and hungry population.

Secondly, North Korea uses its military power as a way to intimidate other countries. As well as its weapons of mass destruction, it has the world’s forth largest army. The aggressive tactics, regular skirmishes with South Korea, and the doom-laden rhetoric that that North Korea regularly uses against its enemies in South Korea, Japan and the USA are all designed to show that the North Korean leadership is determined to fight to the death in order to survive. The implicit threat was that a terminally collapsing regime could decide to go out with a bang rather than a whimper and launch an invasion of South Korea or attack Japan.

Secondly, North Korea uses its military power as a way to intimidate other countries. As well as its weapons of mass destruction, it has the world’s forth largest army. The aggressive tactics, regular skirmishes with South Korea, and the doom-laden rhetoric that that North Korea regularly uses against its enemies in South Korea, Japan and the USA are all designed to show that the North Korean leadership is determined to fight to the death in order to survive. The implicit threat was that a terminally collapsing regime could decide to go out with a bang rather than a whimper and launch an invasion of South Korea or attack Japan.

But even without this, the sudden collapse of North Korea threatened to cause a massive refugee problem as millions of desperate and starving people threatened to destabilise both South Korea and China as they abandoned a failed state. Fearful of both a catastrophic military conflict and the sudden collapse of North Korea foreign countries did a deal with the devil.

But even without this, the sudden collapse of North Korea threatened to cause a massive refugee problem as millions of desperate and starving people threatened to destabilise both South Korea and China as they abandoned a failed state. Fearful of both a catastrophic military conflict and the sudden collapse of North Korea foreign countries did a deal with the devil.

Cynically using the starving North Korean population as pawns in this geo-political game, the North Korean regime demanded food and other aid from foreign countries. Vague promises of reform were made by the North Koreans which they had no intention of keeping.

Cynically using the starving North Korean population as pawns in this geo-political game, the North Korean regime demanded food and other aid from foreign countries. Vague promises of reform were made by the North Koreans which they had no intention of keeping.

As the distribution of the food aid was largely controlled by the regime, they used it to feed the army and also keep control over the population. Loyal sections of the population were rewarded with food – disloyal groups had to fend for themselves. Food was used to regain a degree of control over the population and prevent the country from collapsing. In fairness to the outside world, they were placed in an impossible position; they either had to deliberately let millions starve to death or else send food aid which would enable this brutal regime to survive.

As the distribution of the food aid was largely controlled by the regime, they used it to feed the army and also keep control over the population. Loyal sections of the population were rewarded with food – disloyal groups had to fend for themselves. Food was used to regain a degree of control over the population and prevent the country from collapsing. In fairness to the outside world, they were placed in an impossible position; they either had to deliberately let millions starve to death or else send food aid which would enable this brutal regime to survive.

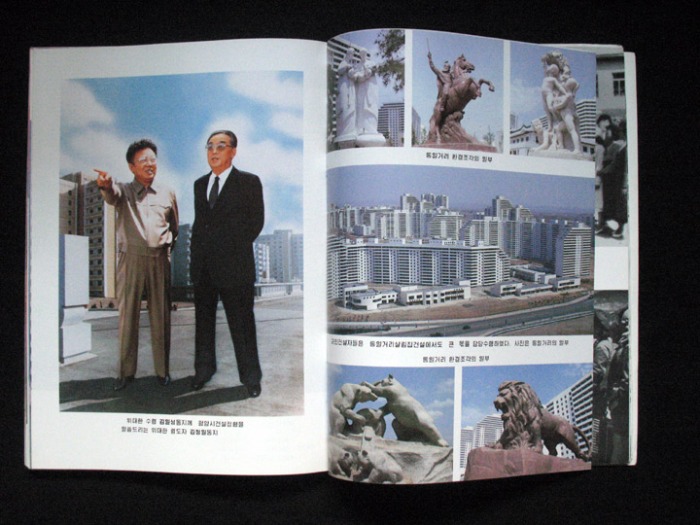

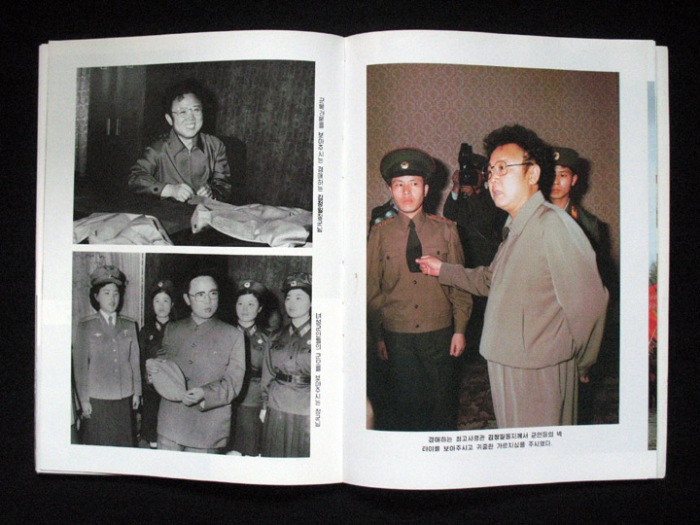

Printed in 1995, one year after the death of his father Kim Il Sung, this book is designed to show how loyal the North Korean army is to the new leader Kim Jong Il. (I don’t speak Korean so I am unable to give the exact title). It begins with the standard myth of Kim Jong Il’s messiah-like birth in a secret camp in Mount Paektu, which also appears on the cover. Then we see images of the younger Kim in training, following in his father’s footsteps as he learns how to run the country as he sets about building a bright future for the people. This is all designed to show a direct continuity between the deceased dictator and the new leader as the only true successor.

Printed in 1995, one year after the death of his father Kim Il Sung, this book is designed to show how loyal the North Korean army is to the new leader Kim Jong Il. (I don’t speak Korean so I am unable to give the exact title). It begins with the standard myth of Kim Jong Il’s messiah-like birth in a secret camp in Mount Paektu, which also appears on the cover. Then we see images of the younger Kim in training, following in his father’s footsteps as he learns how to run the country as he sets about building a bright future for the people. This is all designed to show a direct continuity between the deceased dictator and the new leader as the only true successor.

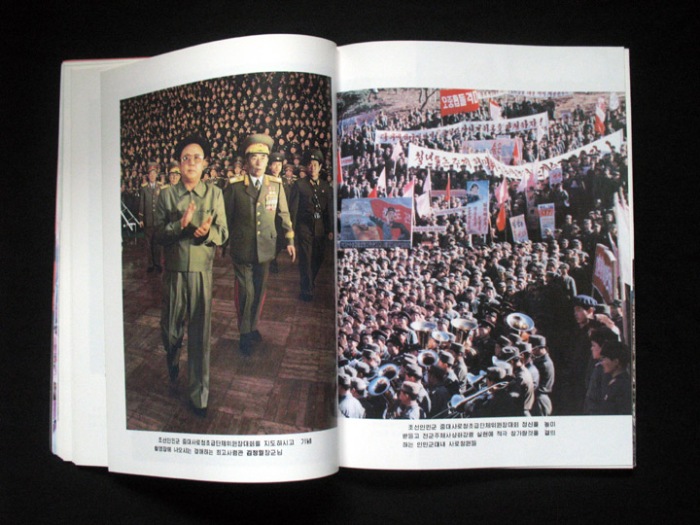

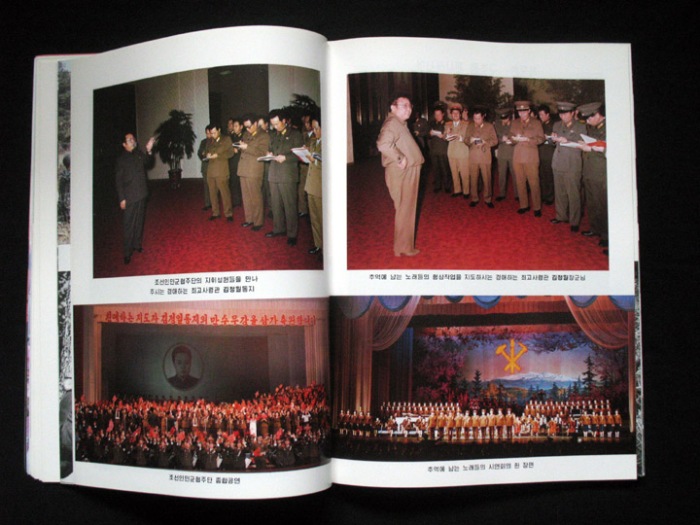

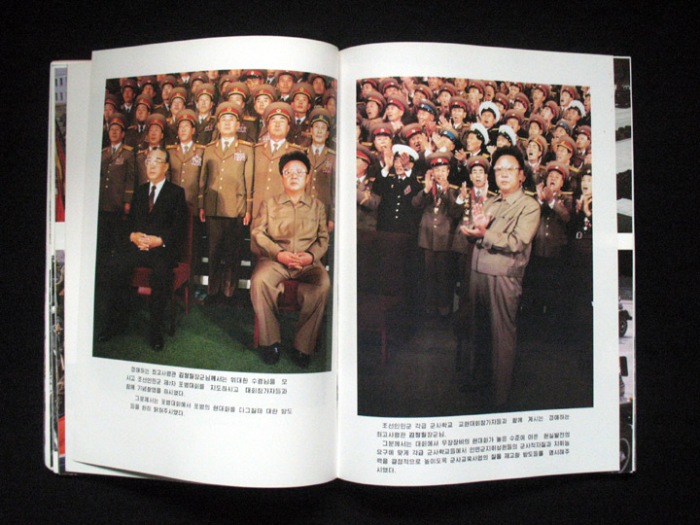

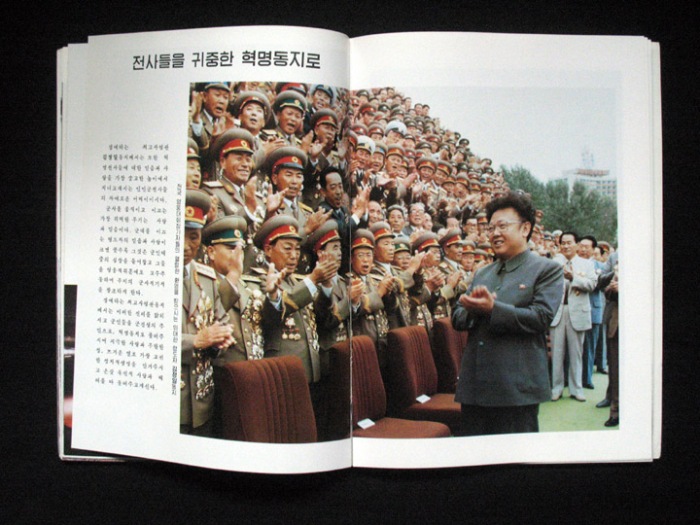

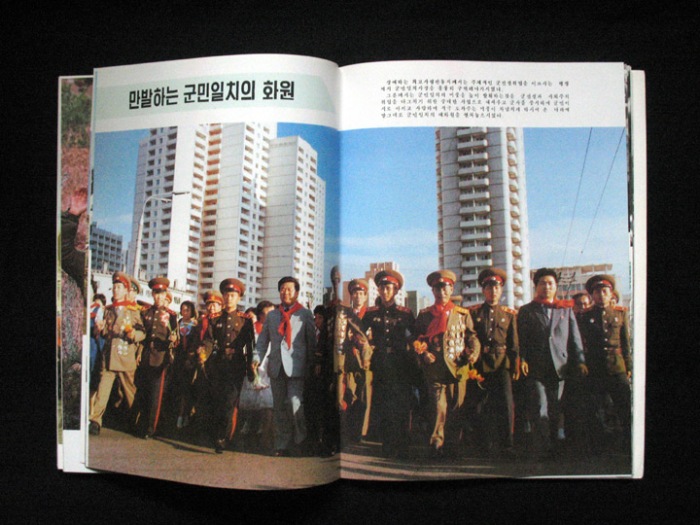

Kim junior is then shown on his own, taking the reins of power as photograph after photograph shows be-medalled generals listening to his every word. Crowds clap and cheer. The Dear Leader is central to all aspects of the armed forces, from planning strategy with his generals to inspecting the ties of soldiers. In a chilling juxtaposition, images of a beaming Kim Jong Il are paired with explosions and other demonstrations of military might designed to show that all power rests with him. The omnipotent leader sees and controls everything.

Kim junior is then shown on his own, taking the reins of power as photograph after photograph shows be-medalled generals listening to his every word. Crowds clap and cheer. The Dear Leader is central to all aspects of the armed forces, from planning strategy with his generals to inspecting the ties of soldiers. In a chilling juxtaposition, images of a beaming Kim Jong Il are paired with explosions and other demonstrations of military might designed to show that all power rests with him. The omnipotent leader sees and controls everything.

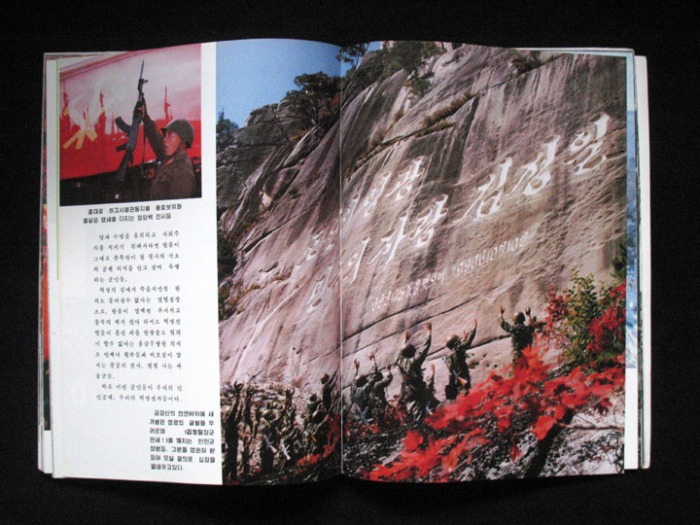

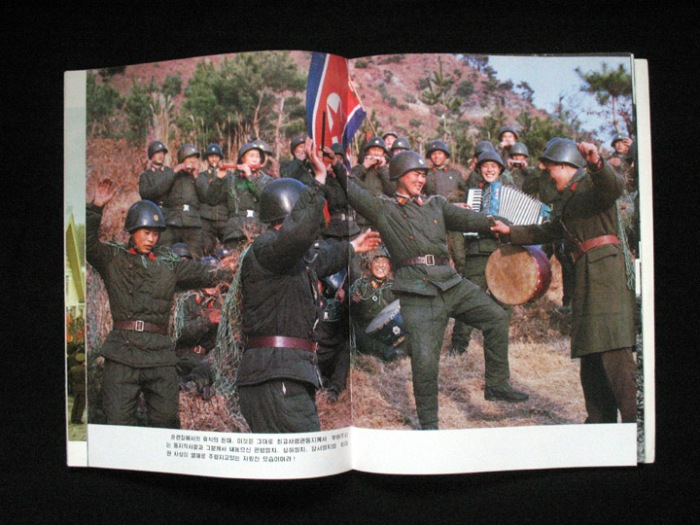

Then the narrative shifts to the lowly soldiers on the ground. As well as the usual images of military might – missiles, tanks, planes and ships at the ready, we see portraits of ferociously screaming soldiers. This is all the more poignant, as the regime deliberately inculcated the idea that ordinary soldiers would be prepared to engage in suicide attacks in fighting against the enemy.This had some veracity as many North Korean spies and infiltrators had committed suicide rather than be captured in attacks in South Korea and Japan.

Then the narrative shifts to the lowly soldiers on the ground. As well as the usual images of military might – missiles, tanks, planes and ships at the ready, we see portraits of ferociously screaming soldiers. This is all the more poignant, as the regime deliberately inculcated the idea that ordinary soldiers would be prepared to engage in suicide attacks in fighting against the enemy.This had some veracity as many North Korean spies and infiltrators had committed suicide rather than be captured in attacks in South Korea and Japan.

Other images show ordinary soldiers expressing their gratitude to the regime, and Kim Jong Il himself, for the happy life they are prepared to fight and die for. Here we see photographs of the showcase capital and the architectural achievements of the regime used to show that they truly care about the welfare of the ordinary people. Young and old are shown united in their complete loyalty to the Kim dynasty as they parade through the streets. Again, the message here is that the entire country is utterly loyal to the Dear Leader. Of the famine, poverty and brutality that pervaded North Korea at that time (and still does), we see nothing.

Other images show ordinary soldiers expressing their gratitude to the regime, and Kim Jong Il himself, for the happy life they are prepared to fight and die for. Here we see photographs of the showcase capital and the architectural achievements of the regime used to show that they truly care about the welfare of the ordinary people. Young and old are shown united in their complete loyalty to the Kim dynasty as they parade through the streets. Again, the message here is that the entire country is utterly loyal to the Dear Leader. Of the famine, poverty and brutality that pervaded North Korea at that time (and still does), we see nothing.

The central message of this book was to convince readers that North Korea’s enemies were facing an utterly fanatical foe who was prepared to stop at nothing in order to survive.

The central message of this book was to convince readers that North Korea’s enemies were facing an utterly fanatical foe who was prepared to stop at nothing in order to survive.

And it worked.