The Victorian era saw an unprecedented urbanisation of society as the draw of factory work (and the promise of supposed riches) lured millions of the young and hopeful away from the backbreaking despair of the countryside. Britain established the model for industrial development that is being used today in China. Throughout the nineteenth century, industrial cities such as Manchester, Birmingham, Sheffield and Glasgow to name a few became the centres of heavy industry and a source of massive wealth for a small group of people. Most of the unfortunates who actually did the heavy, dangerous and backbreaking toil for a pittance were consigned to slums of shoddily built houses with no sanitation, running water or basic amenities. For the dubious privilege of living there landlords charged massive rents to already exploited people.

In Victorian society marked by strict hierarchical division based on class and the appearance of outward respectability, the British middle and upper classes, who were benefitting from this new found wealth, were at first quite happy to ignore the nightmare in their midst. However the dangers of having huge numbers of impoverished, desperate people on their doorstep soon became a source of fear. A new-found concern for the welfare of the poor arouse from the 1840s onwards mainly because it became apparent that the overcrowded slums were breeding grounds of revolution and disease. In particular cholera was the great nineteenth century middle-class nightmare because as well as the potential for death, you couldn’t control your bowel movements, which in a society that was based on outward respectability, was especially ‘embarrassing’.

Into this festering Glaswegian urban mix steps an official local government body, the City Improvement Trust, charged with trying to bring some sort of order to the chaos and provide basic sanitation and living conditions for the urban poor. As part of their work, they intended to knock down and build new houses to replace the overcrowded slums. Obviously the local slum-lords who owned the buildings were not keen on having these meddling do-gooders disturb their very profitable racket and the usual combination of greed, money, politicians, powerful vested interests and bureaucratic red tape made the process of change slow and ultimately futile (clearing the slums didn’t solve the problem – it merely moved it to another area).

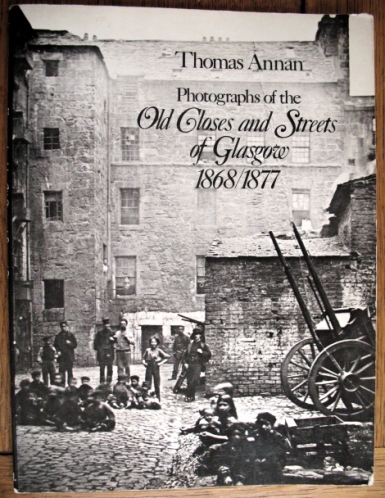

As part of their work, the Trust decided to employ a photographer in 1868 to take photographs of some of the most run-down slums in the city that they planned to demolish and for this they chose a middle-class commercial photographer, Thomas Annan. Annan was employed to provide a visual record of poverty that the Trust could use to convince decision-makers, who would never go into slums, that things needed to change.

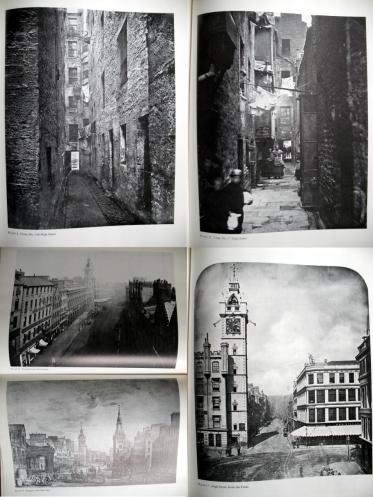

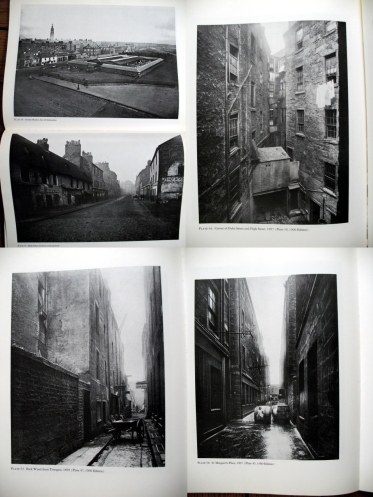

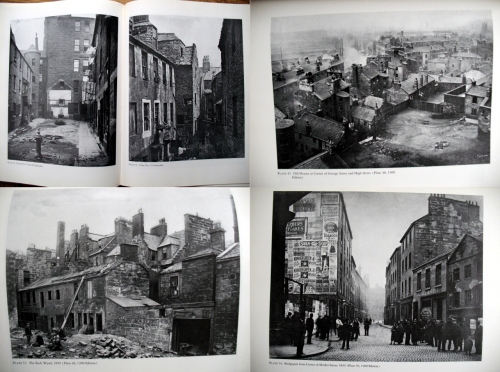

The book I have is a 1977 Dover reprint of the original publication which publishes the original 1868 images Annan took as well as additional photographs made in 1877 and images added in 1900 when it was published as a book (which can be bought on Abe if you have a spare $9,700 burning a hole in your pocket). Most of the additional images added in 1900 were picturesque scenes of old town life, indicating to me that nostalgia had already set in when the book was finally published. The photographs of 1868 were documenting an immediate problem for a bureaucracy; by 1900 they were safely consigned to the past.

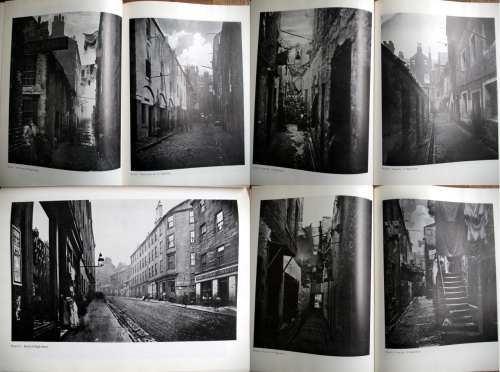

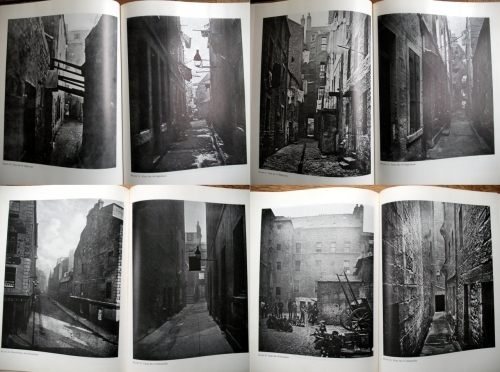

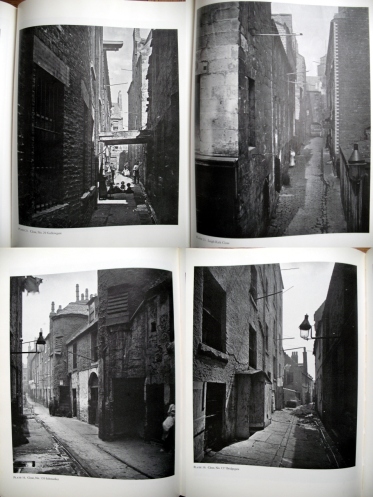

It is the original 1868 photographs of the alleyways that really stand out. The photographs are for the most part uniformly gloomy and sinister; the sky is a small muddy grey patch in the corner of the frame. In the Victorian imagination, light is associated with order and progress; dark is backward and dangerous. The images emphasise the dark, claustrophobic nature of the alleyways and courtyards where thousands of people lived cheek by jowl in absolute poverty. This is the alleyway where we all fear to tread come to life. Disease in the Victorian imagination was thought to be caused by bad air (miasma) and dark unventilated conditions were thought to cause epidemics. Looking at the photographs in this way, what the Victorian viewer saw was the perfect breeding ground for crime, disorder, violence and disease, giving them a personal incentive to buy into slum clearance efforts.

It is important to remember that we are looking at these photographs from a totally different perspective. They are records of a distant past which is alien to us. Middle class viewers of the time would have been horrified and fascinated at the sight of these dangerous spaces. Respectable people did not go anywhere near these areas. The slums were an unknown black hole in the middle of a city. Annan is the original disaster tourist venturing into dangerous places where the ordinary person fears to tread in order to bring back the ‘truth’ of what he sees there to a distant audience. Because of the technology of the day, Annan’s photographs took time to make and in many of them we can see the blurred outlines of people looking curiously at the unusual sight of the photographer. But he is no Riis or Hine concerned with documenting injustice. Annan is here to photograph the architecture. The buildings are Annan’s focus; the inhabitants who live in them are not his concern. Although slum-dwellers may appear in his photographs they are as much a part of the scenery as the washing lines that pepper Annan’s images.

The poor, it seems, will always be with us.

Reblogged this on Ignoramuses guide to Independence.

Reblogged this on Photographia.