Iraq has dominated the Western imagination since the 1990s. Saddam Hussein’s brutal dictatorship was more than tolerated during the simplistic polarisation of the globe into capitalism/communism that prevailed after the Second World War. But that model changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Then, following Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in order to replenish its coffers after a futile decade-long war against Iran, Saddam became the test case of the new post Cold War Pax Americana. (The triumphal hyperbole during the first half of the 1990s knew no bounds with commentators declaring that a New World Order had been created and even stating that the End of History was in sight – all nonsense of course.)

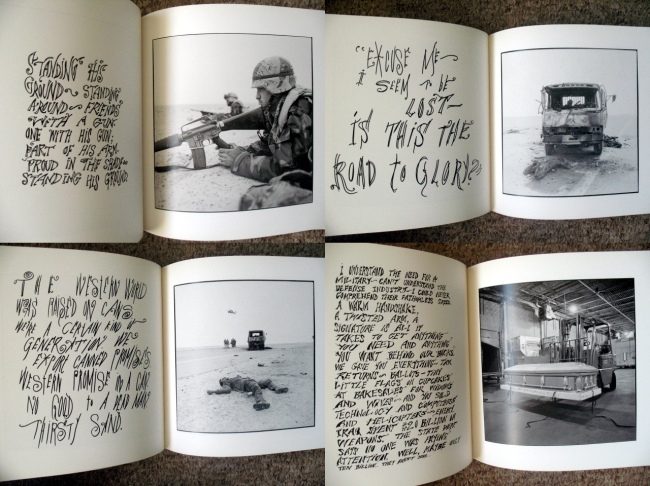

The 1991 Gulf War showed just how far the US military and political establishments had come in devising strategies to control and censor information in order to maintain public opinion. Key to this was the promulgation of a simplistic narrative about a crazed dictator and a coalition of allied nations uniting to free an occupied land and people (a strategy that clearly appropriated themes from the Second World War and distanced this conflict in the public mind from Vietnam). Even the names, such as Stormin’ Norman leading Desert Storm, were carefully chosen to resemble something out of a cheesy 1980s Schwarzenegger/Stallone action movie, familiar to audiences of the period, with a simplified plot, clear distinctions between the good/bad guys and a moral relativism that celebrated the use of violence on the part of the good guys but condemned the bad guys when they behaved in the same manner.

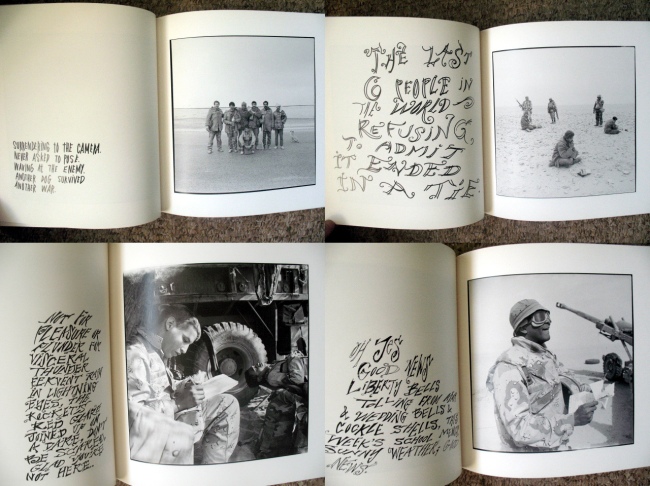

After Vietnam, reporters and photojournalists were regarded as threats and potential enemies who might undermine the carefully managed fiction being produced by the military and political spin-doctors. Therefore they were carefully managed throughout to ensure that what they reported didn’t contradict the overall message of a bloodless war. Although CNN provided constant coverage of the conflict on a scale heretofore unknown, the imagery produced was surprisingly limited. Lots of soupy green night-vision video from the roof of Baghdad’s Rashid Hotel and carefully chosen footage from so-called smart bombs hitting their targets with pinpoint accuracy were the motifs of this war for a distant audience. This produced a distancing effect, turning it into a video-game that precluded any identification on the part of the viewer with the end results produced. Death and suffering were subjects that were conspicuous by their absence in this spectacular display of power.

In this tightly controlled environment, very few images managed to depict the carnage caused by the much-lauded smart bombs that had convinced the Western world that it could engage in war without consequence. While the war went on for over a month, it was only towards the end of the period that images showing the effects of war emerged. In particular, Kenneth Jarecke’s searing image of a badly burnt and disfigured Iraqi soldier sitting in the cab of a truck has assumed an importance insofar as it undermines the officially sanctioned narrative.

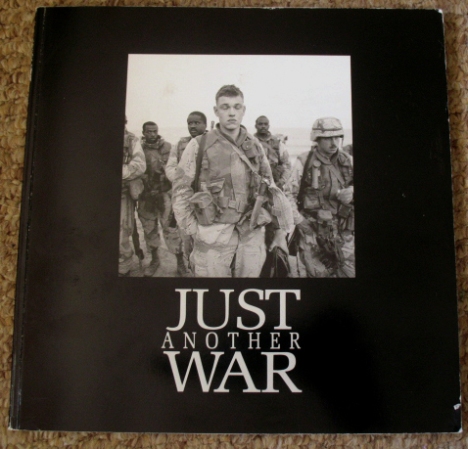

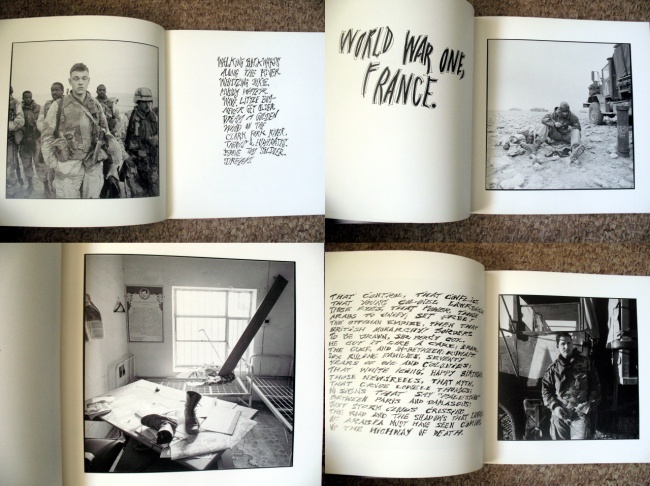

Published in 1992 by Bedrock Press, this book is a collection of images taken by Jarecke alongside texts by Exene Cervenka and is one of the few photobooks to emerge in the aftermath of the first Gulf War that criticised the narrative of a (then) very popular war at a time when challenges to US global power were almost non-existent. The largely celebratory manner by which the first Gulf War was represented contributed, in part, to US public support for the second war against Iraq in 2003 because it was assumed that it would also be a quick and easy victory, the carnage would remain unseen, and American casualties would remain light. That proved not to be the case.

Published in 1992 by Bedrock Press, this book is a collection of images taken by Jarecke alongside texts by Exene Cervenka and is one of the few photobooks to emerge in the aftermath of the first Gulf War that criticised the narrative of a (then) very popular war at a time when challenges to US global power were almost non-existent. The largely celebratory manner by which the first Gulf War was represented contributed, in part, to US public support for the second war against Iraq in 2003 because it was assumed that it would also be a quick and easy victory, the carnage would remain unseen, and American casualties would remain light. That proved not to be the case.

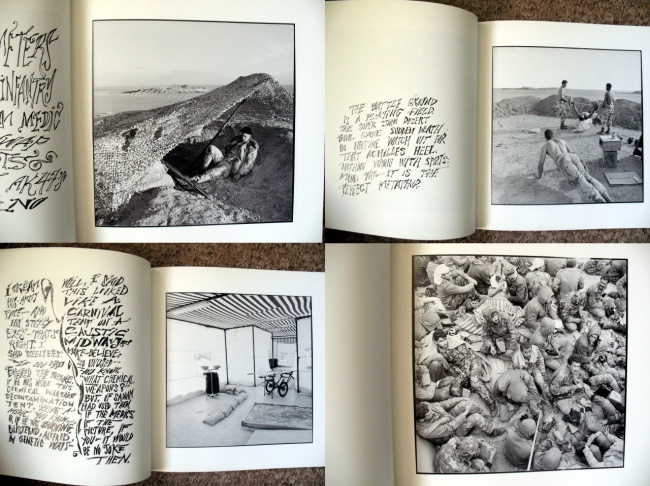

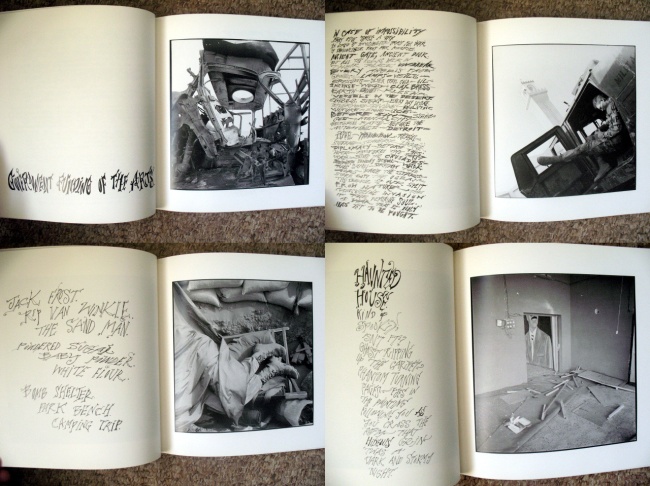

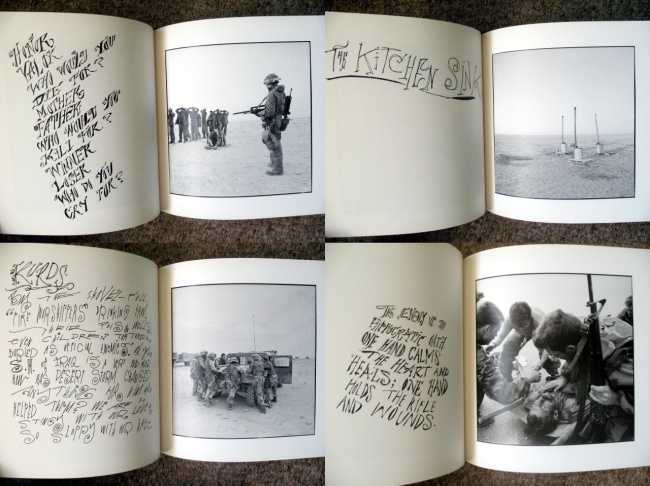

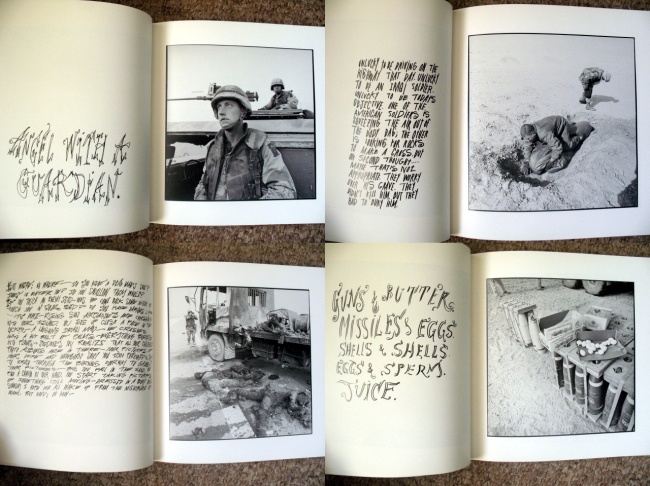

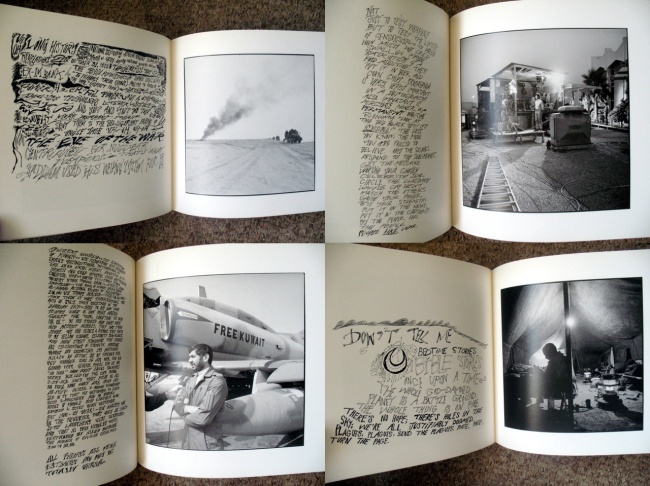

Dispensing with the standard 35mm format that was the camera of choice for photojournalism at the time, Jarecke presents a series of square format black and white images depicting his experiences during the war. Printed in high-key, due to the harsh light of the region, much of the photographs depict coalition soldiers either during periods of boredom or inaction, echoing the fact that photographers were kept well away from the realities of warfare. This also reflected that for much of the conflict, the actual soldiers had nothing to do as the air bombardment of Iraqi forces went on for a month before the famed 100 hour land offensive occurred. Thus, for photojournalists with the coalition forces the effects of this warfare remained almost totally invisible until the last few days of the war and by then the smart-bomb/night-vision narrative produced by the media had become firmly embedded in the public consciousness. The new technology of Western warfare was celebrated while the consequences remained invisible.

Jarecke’s images are combined with texts, of differing lengths, on the facing page by Cervenka that serve as an immediate personal response and a deeper critique of the jingoistic narrative, whilst attempting to place this conflict in a historical perspective. Certainly, from a typographical point of view, the text is very effective, producing a very personal commentary on both the photographs and the war itself. Cervenka’s text operates to contextualise the war, dissecting the simplistic narrative produced by the cheerleaders of Western power, tracing it back to the decisions made by now defunct colonial powers in the aftermath of the First World War. These decisions had the effect of destabilising the region in the pursuit of imperial ambitions that have long since been consigned to the dustbin of history. Cervenka also examines the ambiguous relationship between Saddam’s Iraq and the United States in the decades prior to the war, the military-industrial complex and an oil dependent economy.

Jarecke’s images are combined with texts, of differing lengths, on the facing page by Cervenka that serve as an immediate personal response and a deeper critique of the jingoistic narrative, whilst attempting to place this conflict in a historical perspective. Certainly, from a typographical point of view, the text is very effective, producing a very personal commentary on both the photographs and the war itself. Cervenka’s text operates to contextualise the war, dissecting the simplistic narrative produced by the cheerleaders of Western power, tracing it back to the decisions made by now defunct colonial powers in the aftermath of the First World War. These decisions had the effect of destabilising the region in the pursuit of imperial ambitions that have long since been consigned to the dustbin of history. Cervenka also examines the ambiguous relationship between Saddam’s Iraq and the United States in the decades prior to the war, the military-industrial complex and an oil dependent economy.

But what really made Jarecke’s visualisation of this war stand out was his iconic image of the blackened, incinerated body of an Iraqi soldier bent over a steering wheel, framed by the empty windscreen of a burnt out truck. As well as being one of the few images that depicted the realities of high-tech warfare (and showed that the end result was just as brutal as ever) the photograph was particularly effective in that the anonymous man’s gaze met that of the viewer, staring out in a grimace of unimaginable agony. According to Jarecke, they came across a single truck on a highway which had been recently attacked from the air. While that single image has assumed an iconic status and has become one of the few depictions to challenge the official rhetoric, the book contains a number of other images made of the same scene. (It was only published by the Observer newspaper at the time – Time magazine wouldn’t touch it despite Jarecke being under contract to them.) If the news media found printing that particular image problematic, then the other photographs Jarecke made had no chance of appearing in newspapers. The horrific realities of so-called smart-bombs are laid bare in these few images of disembodied corpses representing undermined the video-game/action-movie narrative adopted by the media. If the authorised narrative privileged distance and the elevated perspective of technological awe, then Jarecke’s images depict the grim results on the ground. But from the American military’s perspective, they achieved their objective of maintaining public support for the war through tightly controlling how it was represented to a distant audience. This strategy would have profound implications for the future.

Thanks for another good post, I really like the way you interconnect a book to the history of society. And this book looks great in its style of a double entry (text and photos) diary.